The Legend of KOPS

Updated 2025-10-11 with information from Hinault's book

Current bike fit trends (both on road and off) have riders moving forwards on the bike. At some point in any online discussion, the topic of the old fit rule "Knee Over Pedal Spindle" (KOPS) will come up, and usually by someone referring to an article written by framebuilder Keith Bontrager. Titled "The Myth of KOPS", it was published in Bicycle Guide in the 1990s then later was transcribed and published on Sheldon Brown's web site, a modern reference guide for all things cycling.

Unfortunately, once it was on the internet it was skimmed by Internet Bike Experts who rushed to tell others that KOPS was "debunked". This lead me to wonder, was it? Especially since Bontrager concludes in the article that "It usually puts the rider in the range of correct fit". It also doesn't help that he says about his alternate method: "This explanation will never be a commercially viable fitting technique. It is too complicated. ... Simple methods like the traditional ones will be more useful".

It's hard to judge his system since he doesn't publish his methods, and we don't know the error of how he measured his inputs. But there's no need to debunk his debunking - his article is good enough as a thought experiment that shows that if you want to determine the rider's fore-aft position there's justification that a simple vertical knee-pedal relationship is an oversimplification. He says as much in the introduction: his motivation to write it was driven by customers concerned that he wasn't using this supposed "rule".

This also led me to wonder, what exactly is the KOPS we are "debunking"? Where did it come from, and what does it really say?

In his introductory notes (written years after first penning the article), Bontrager mentions the method coming from the Fit Kit system. I have been trying to find an original copy of the Fit Kit manual to see what says, but haven't found a copy yet. I went to the internet to see if I could find other references.

The first mention of the phrase "knee over pedal spindle" in Google Books is in "Greg LeMond's Complete Book of Cycling" written in 1987. LeMond sums up the method as:

To set up your pedal position, move the saddle back as far as it will go. Get on the saddle and drop a plumb line from the front of your kneecap. If the plumb line bisects the center of the pedal or falls about a centimeter or so behind, you've got the right pedaling position. Anything else is wrong. (p. 144)

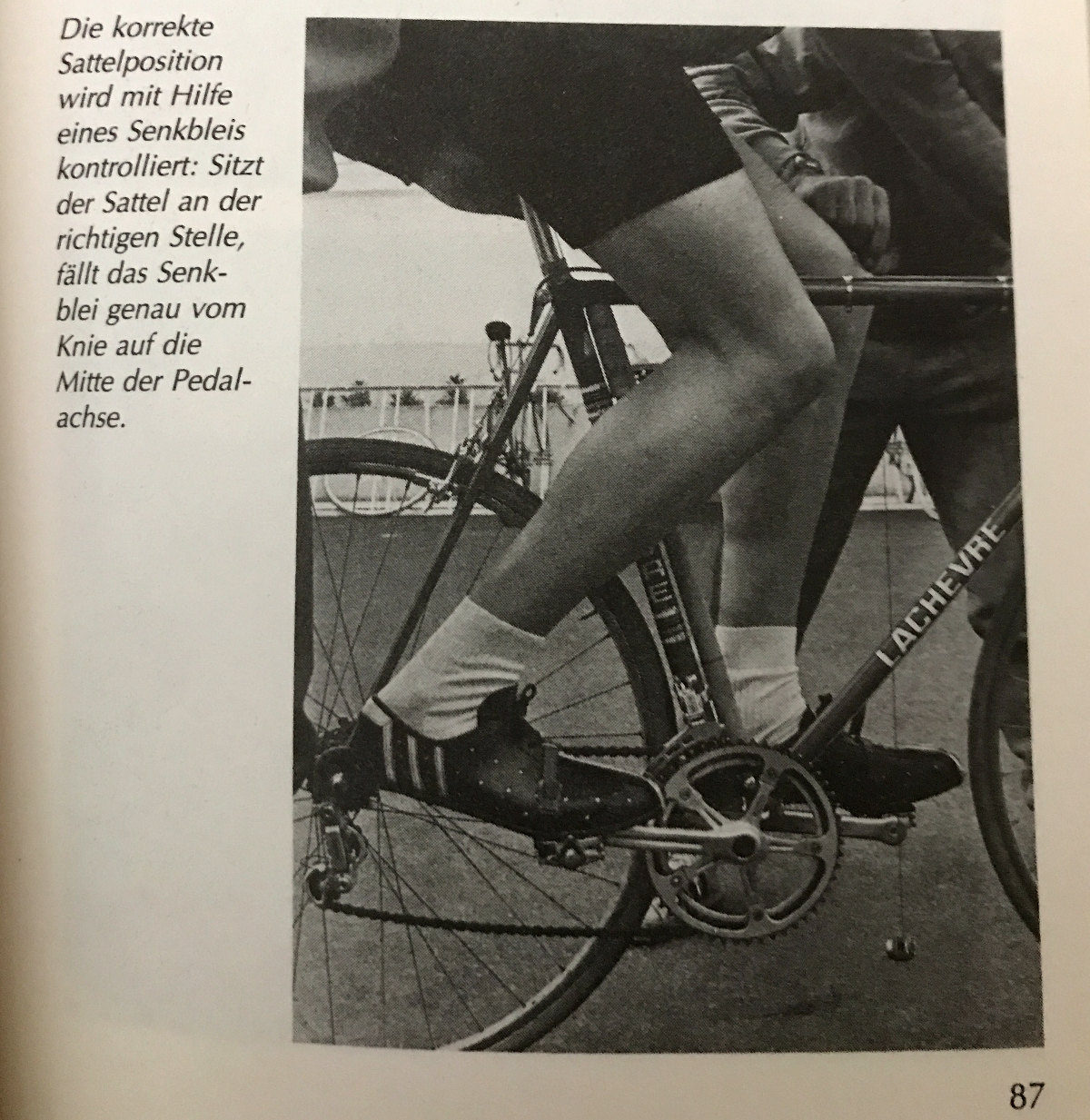

In the fitting section LeMond also recommends the saddle height equations developed by his coach Cyrille Guimard. Guimard also wrote a book in 1977. I have the German edition, and the plumb bob from the front of the knee to the pedal spindle is shown on pages 86 and 87. I don't believe the book was translated to English so that may explain why the English phrase doesn't show up until Lemond's book.

A year before Lemond's book, his former teammate Bernard Hinault also wrote a cycling book in French. It was translated to English in 1988. It mentions KOPS in a section called "The traditional ways of setting position" (pp. 67), but asthe phrase "Plumb line from the kneecap". The method is attributed to the French national cycling coach Daniel Clement and quotes him as defining the target point as the end of the femur (or the hollow beheind the kneecap). However Hinault's book advocates for the position to be further back to get more of a push over the top of the stroke, and considers it only good as a starting point that is likely too far forwards. Given that Hinault and Lemond were teammates, it's not surprising to see Lemond shooting for a further rearwards position by using the front of the kneecap.

In other English-language books I have looked at from before 1987, if a plumb bob makes an appearance it's to measure the saddle setback behind the bottom bracket. For example, in the 1980's "The Bicycle Touring Book", the authors suggest the saddle should be set back "between 1 1/2 and 3 inches" (p.45) This method will have different measurements depending on how high the saddle is and seems to have little value, but it also appears in the famous CONI Manual so I suspect many authors used it as a reference.

In later references, the position seems to have shifted forward from Lemond's rearward preference. Some books continue to use the front of the kneecap but aim for the front of the shoe instead of the pedal spindle. Others change to reference points on the knee further back. In "The Complete Bike Book" from 2003, the advice is to position "the end of the femur (the depression in the side of your knee ... directly over the spindle". Others pick the tibial condolye or tuberosity. Choosing a point near to the pivot point of the knee and placing it directly on top of the pedal spindle makes some sense if only the load always came from gravity pointing down.

At some point KOPS becomes gospel - even showing up in physiology papers as the "right" way to fit a bike. For example, in the paper "The Need for Data-driven Bike Fitting: Data Study of Subjective Expert Fitting" by Braeckevelt et al (2019) (link), the authors state:

For the lower body, two general rules exist in bike fitting. These are respectively the safe knee angle range and the Knee Over Pedal Spindle (KOPS) technique. KOPS is defined as the distance that the patella comes over the center of the pedal spindle when the pedal is at the 6 o’clock position. Correct adoption of these two basics should ideally result in tight ranges across the different bike fits.

Note that this paper picks the patella as yet another reference point!

Returning back to LeMond, he says his positioning is "more efficient and comfortable" (p. 137). There is no mention of power from saddle positioning. The seat height section gets the credit for optimizing power. LeMond even has the rider readjust saddle height as the saddle is adjusted forwards to arrive at KOPS so that power is not lost.

In a way, LeMond's methods around fore-aft position are a guard against bikes that are too steep and don't fit. He starts the rider with the saddle all the way back and states that if the knee is past the pedal the rider should seek out a different frame with a slacker seat angle. Unfortunately instead of trying to determine a good balance experimentally (often referred to as the Kirk method he only has the rider move forwards until KOPS is achieved.

In the CONI manual, fore-aft position only follows general ranges that vary between 1 and 6.5 cm behind the bottom bracket. Ironically, most of this range would not pass the current UCI 5cm saddle setback rule!

The saddle is placed forwards or back according to the type of race for which the bicycle is intended and also to the cyclist's constitution... The bringing forward of the saddle by the cyclist in action should be adapted to the aptitude of the cyclist himself. (p.146)

While the CONI manual has many numerical guidelines, it always seems to say in effect, "put the saddle where the rider needs it".

Methods later appeared to determine fore-aft position by looking at the rider's balance. Dave Kirk's blog posting mentioned above is cited enough to be a good candidate for the origination of this technique. These methods adjust the saddle position so the rider can pedal under moderate force and support their upper body without their arms. It does assume the balance is needed to spare the rider's arms - once the torso is supported on aero bar pads the relationship has less value.

Knee-to-toe relationships also show up in other areas of sport, most notably as a technique cue for squats and deadlifts. I don't have a lot of knowledge in this world so the best I can do is say that it appears that by trying to keep the knees behind the toes when squatting, you keep your back flatter and lift more from the glutes.

Researching the squat connection I ran into a YouTuber called "Knees Over Toes Guy". I'm not sure if he's trying to debunk the knee relationship in squats or just has some different ideas on how to strengthen your knees. In reading about him I found some fans point to studies that point to low knee load and high hip load when you keep your knees back, like the high hip load is therefore bad. But isn't that the point - to use your glutes more effectively? I don't really know enough to have an opinion and of course then I found a bunch of people getting into contrasting "knees behind toes" exercises and just got confused by the whole thing. There might be some interesting things to follow up in this world if I get really motivated.

There are some theories that since we have gait so hardwired into our nervous systems that the body is using the knee's position relative to the foot to trigger some part of the walking motion. A knee too far forwards could be interpreted that we're falling forwards and it's time to get the trailing foot moving to catch the next step. This might inhibit the muscles that are still trying to perform a less natural pedalling motion.

The nervous system may also interpret a forward knee as being unstable and more vulnerable to damage and attempt similar preventative measures. Since our inner ear can tell the brain which way is "down" then maybe there is some importance to the direction of the pedal force. These protective instincts may not be as strongly triggered in a recumbent position.

So what can we conclude here? We can certainly say your fore-aft position is an important factor in bike fit. The rule of KOPS seems to be so broadly interpreted there's as much variation there as there is for the general setback guidelines. As a quick rule, I'd probably say you're looking for KAOS (Knee Aft Of Pedal) but if you're going to be adjusting the saddle forwards and back you might as well just use a balance test instead.

Any single rule is insufficient anyway - moving the seat back closes the hip angle which then needs higher bars or shorter cranks, and then those changes cascade into even more changes. In the end you need a holistic view, not a simple rule to follow. I'm with the CONI manual - you need to put the seat where the rider needs it!